Phishing Email Alerts – 100th Edition

Catch of the Day:

Chef’s Special:

This is the 100th edition of the Friday Phish Fry. Two years ago we started publishing these weekly examples of clever phish that made it past my spam filters and into my Inbox, or from clients, or reliable sources on the Internet.

I would be delighted to accept suspicious phishing examples from you. Please forward your email to phish@wyzguys.com.

My intention is to provide a warning, examples of current phishing scams, related articles, and education about how these scams and exploits work, and how to detect them in your own inbox. If the pictures are too small or extend off the page, double-clicking on them will open them up in a photo viewer app.

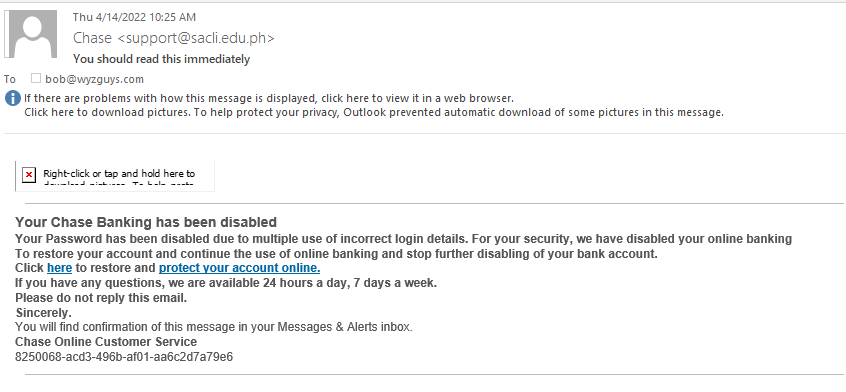

Chase Phish

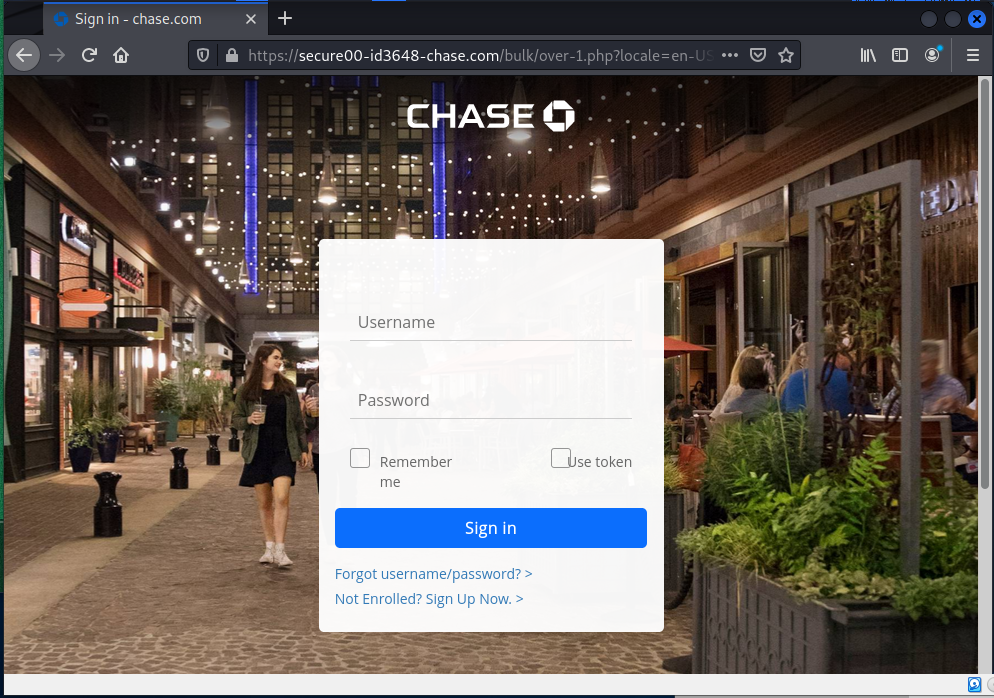

Here’s another shot at stealing my banking credentials, this time for a Chase account I don’t even have. The links in the email resolve to https://rebrand.ly/2j23xfn which is redirected to https://secure00-id3648-chase.com/bulk/over-1.php?locale=en-US&authID=59239058c864a2686343ec4e86330eccc0b1d3de&start=1649952163&end=114981534

The important take away is the apparent chase.com address. But this domain includes all the characters secure00-id3648-chase.com. The dashes or hyphens do not create subdomains, like the would if they were periods. The whole think is the registered domain name, and a good attempt at a lookalike domain.

The landing page is nicely executed and looks pretty realistic. When I tried to enter my user name and password, I got an error message, so this Phishing exploit did not try to get much more information, like the recent Wells Fargo exploit we looked at two weeks ago on April Fool’s Day.

Hard-boiled Social Engineering by a Fake “Emergency Data Request”

Bloomberg has reported that forged “Emergency Data Requests” last year induced Apple and Meta to surrender “basic subscriber details, such as a customer’s address, phone number and IP address.”

Emergency Data Requests (EDRs) come from US law enforcement authorities. But don’t they need a warrant to ask for this kind of information? Yes, normally they do. Brian Krebs explains, “In the United States, when federal, state or local law enforcement agencies wish to obtain information about who owns an account at a social media firm, or what Internet addresses a specific cell phone account has used in the past, they must submit an official court-ordered warrant or subpoena.”

And what about tech companies like Apple and Meta? Don’t they know how to receive and respond to warrants? Again, yes, they do. Krebs explains further: “Virtually all major technology companies serving large numbers of users online have departments that routinely review and process such requests, which are typically granted as long as the proper documents are provided and the request appears to come from an email address connected to an actual police department domain name.”

So, what’s going on with EDRs? They’re a bit different. They’re issued in special circumstances by law enforcement agencies when the authorities are concerned about a clear, imminent danger, and they can be issued without the usual legal and judicial review.

As Krebs puts it, “But in certain circumstances — such as a case involving imminent harm or death — an investigating authority may make what’s known as an Emergency Data Request (EDR), which largely bypasses any official review and does not require the requestor to supply any court-approved documents.”

This is the proverbial ticking time bomb, when law enforcement needs information immediately because the threat is both imminent and grave. And of course, a company receiving that kind of request wants to comply. No one wants mayhem, especially mayhem their cooperation might have prevented, and so the recipient is likely to choose responsive, quick disclosure over insistence on procedural privacy safeguards.

Unfortunately, it’s difficult to determine whether an EDR (which, remember, is by its very nature an emergency measure designed to bypass ordinary procedures) is real or not. “It is now clear that some hackers have figured out there is no quick and easy way for a company that receives one of these EDRs to know whether it is legitimate,” Krebs writes.

“Using their illicit access to police email systems, the hackers will send a fake EDR along with an attestation that innocent people will likely suffer greatly or die unless the requested data is provided immediately.”

Thus urgency, here as in so many other cases, seems to have served to lower the victims’ guard. None of the companies who were affected by the scam are without experience in handling requests from law enforcement, and they all have policies in place to prevent this sort of thing from happening.

The social engineers found the procedural gap and drove through it. Changes to policy, and especially some reliable and fast means of authenticating EDRs, should help alleviate the problem.

CONTINUED with links::

https://blog.knowbe4.com/social-engineering-by-emergency-data-request

Exploiting Trust in reCAPTCHA

Researchers at Avanan warn that attackers are using reCAPTCHAs on their phishing sites to avoid detection by security scanners.

“One of the main tasks of reCAPTCHA challenges–those annoying image games you have to play before proceeding to a site– is to make content inaccessible to crawlers and scanners that do not pass the verification process; therefore, the malicious nature of the target websites will not be apparent until the CAPTCHA challenge is solved,” the researchers write.

“Further, because the content of this attachment is a seemingly harmless reCAPTCHA, and the mail client will not be able to solve the CAPTCHA, the email client will have no way of determining the safety of the actual attachment’s content. Adding to the challenge for scanners is that the email is being sent from a legitimate domain, in this case, a compromised university site.”

Avanan explains that reCAPTCHAs also add legitimacy to the sites from a user’s point of view, since many legitimate sites use this feature.

“To the end-user, this doesn’t seem like phishing but more like a nuisance,” the researchers write. “Given how often the average user fills out a CAPTCHA challenge, it’s not out of the ordinary. Neither are password-protected PDF documents. Plus, the PDF is hosted on a convincingly-spoofed OneDrive page, adding another veneer of legitimacy. By providing end-users with innocent enough content, and scanners with enough to be fooled, this is an effective attack for hackers to pull off.”

The phishing links are distributed in emails that purport to contain a faxed document. Avanan offers the following advice for organizations to defend against these attacks:

- Encourage end-users to check URLs before filling out CAPTCHA forms.

- Ask recipients if the PDF should have been password protected.

- With a faxed document, ask the sender if they were in the office or working from home. If working from home, the odds are that they did not fax it.

Blog post with links:

https://blog.knowbe4.com/exploiting-trust-in-recaptcha

Share

APR

About the Author:

I am a cybersecurity and IT instructor, cybersecurity analyst, pen-tester, trainer, and speaker. I am an owner of the WyzCo Group Inc. In addition to consulting on security products and services, I also conduct security audits, compliance audits, vulnerability assessments and penetration tests. I also teach Cybersecurity Awareness Training classes. I work as an information technology and cybersecurity instructor for several training and certification organizations. I have worked in corporate, military, government, and workforce development training environments I am a frequent speaker at professional conferences such as the Minnesota Bloggers Conference, Secure360 Security Conference in 2016, 2017, 2018, 2019, the (ISC)2 World Congress 2016, and the ISSA International Conference 2017, and many local community organizations, including Chambers of Commerce, SCORE, and several school districts. I have been blogging on cybersecurity since 2006 at http://wyzguyscybersecurity.com